One of my favorite tournaments at the Boylston Chess Club is the annual Herb Healy Open House held every New Year’s Day. You get to socialize and play four relatively quick (G/40) games of chess, and there’s an unrated section if you stayed up too late the night before. This year I played in the unrated section as usual and had four interesting games. Let’s take a look!

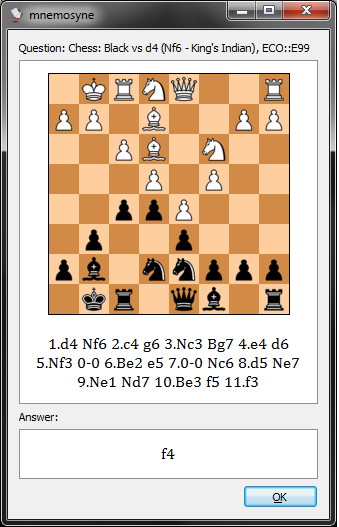

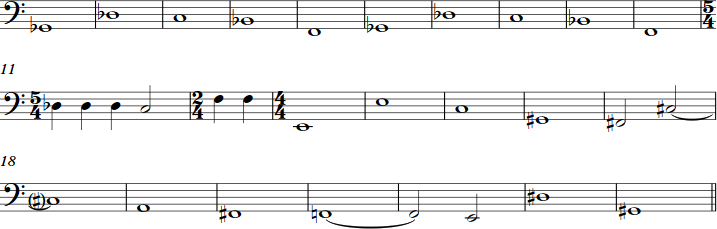

In the first round, my opponent and I both fumbled around through a weird opening move order until we ended up in a King’s Indian sideline that neither of was familiar with.

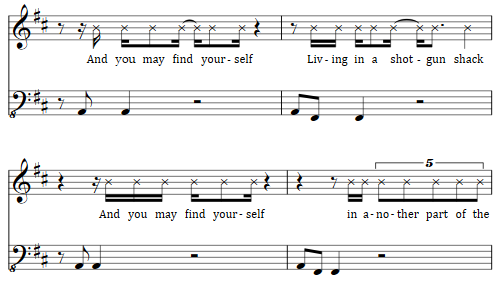

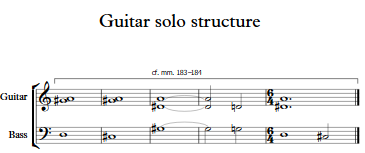

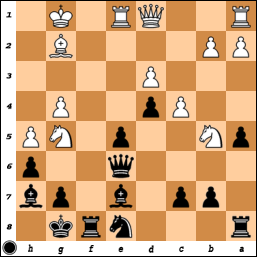

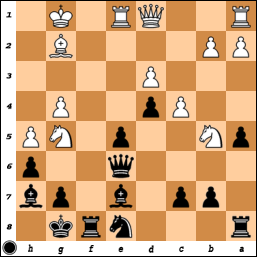

Schmidt 2003 – Rood 1634 after 11.Ra1-d1

I think that this position illustrates a frequent 2000 vs 1600 phenomenon. As White I haven’t done anything super tricky yet, but all my pieces are developed and ready to take action in the future. Black’s pieces are scattered all over the place; his queen and bishop haven’t moved yet and his knight on a6 isn’t much better. One of the things I feel I’ve gotten much better at in the last couple of years is just putting my pieces on good squares and seeing what opportunities present themselves instead of constantly pressing and trying to make things happen before I’m fully developed.

Black tried to get a little more developed with 11…Bd7? but this takes a retreat square away from the knight on f6 and leaves the bishop in a spot with two possible attackers and only one defender. After 12.e5! Black’s only reasonable move is 12…Nh5 but that’s clearly not what he wants to be doing in this position. After 12…Ng4? 13.Bf4! there was no way to avoid losing a piece to the upcoming h3. He resigned a few moves later.

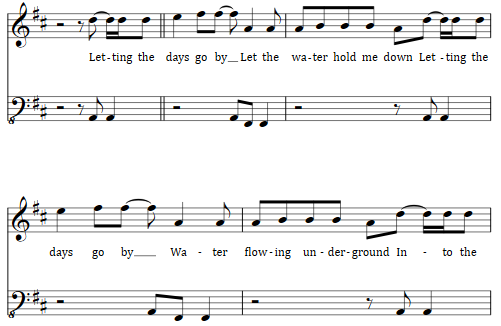

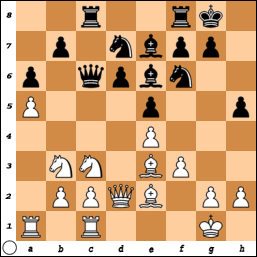

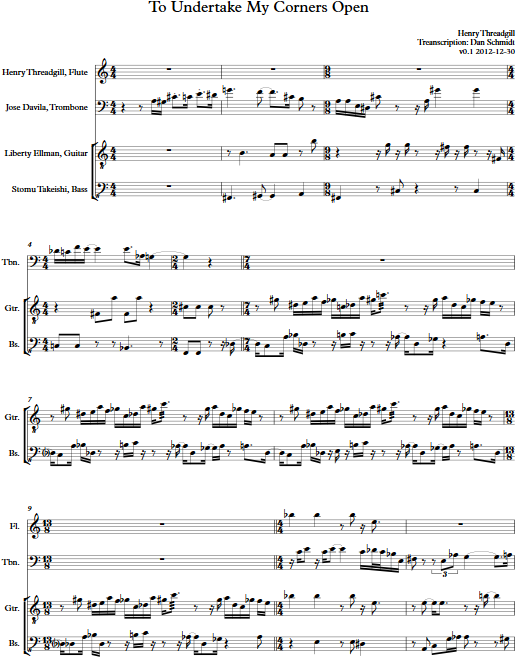

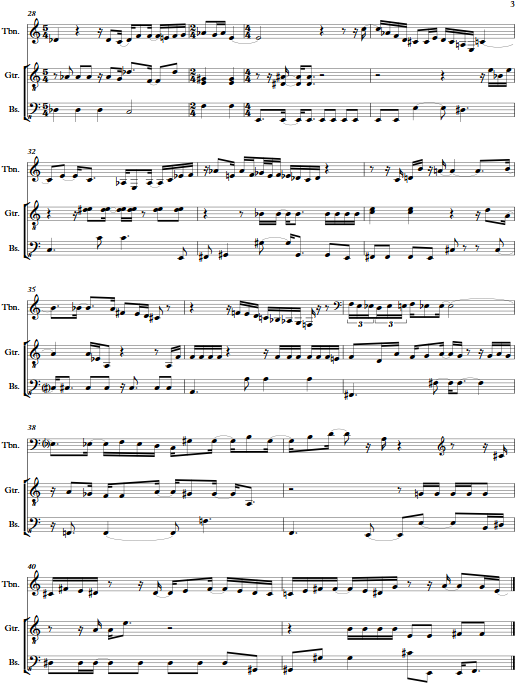

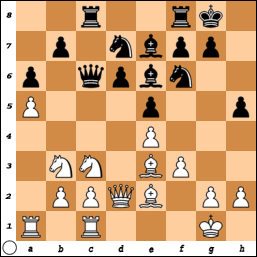

In round 2 I ended up in a weird kind of reversed Benoni position and I found myself on the defensive, with my pieces rather tied up. The tide started to turn in the following position:

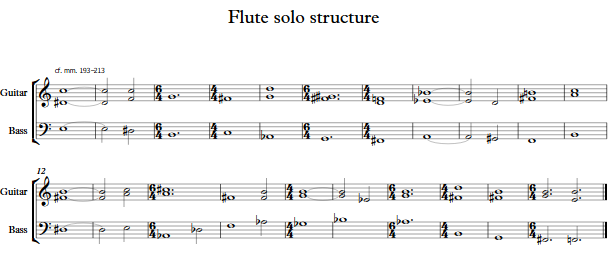

Huntington 1916 – Schmidt 2003 after 17.Ng5-e4

White’s been making me rather unhappy with threats against my d4, c7, and b7 pawns all game. Searching for a way to untangle myself, I looked in desperation at 17…Nd8! and was surprisingly pleased with what I saw. Moving the knight frees me to play …c6, blunting the effect of White’s light-squared bishop, removing a target from c7, and forcing White’s b5 knight back. I also protect the b7 pawn in the meantime so White doesn’t have any tricky discovered attacks against it. Despite all those pieces on the back rank, I finally felt really good about my position and expected to bounce back off the ropes with great force.

White went all in with 18.h5 Bh7 19.Be5, attacking the d4 pawn, but I hadn’t thought this would work. After 19…Ne6 20.f4 f6 (my point; the bishop is trapped) 21.f5 fxe5 22.fxe6 Qxe6, I was already pleased with my extra pawn when White suddenly played 23.Ng5!?

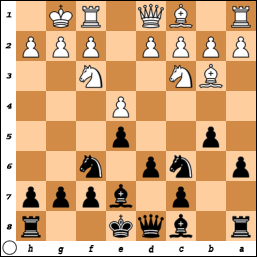

Huntington 1916 – Schmidt 2003 after 23.Ne4-g5

Yikes! After 23…hxg5 White pins and wins my queen with 24.Bd5. For a while I thought I was in big trouble; if 23…Qf6 24.Bd5+ Kh8+ 25.Nf7+ Rxf7 White has 26.Rf1, which looked like it would win the exchange once I moved my queen. But then I realized I could just take on f1 with with 26…Qxf1+ 27.Qxf1 Rxf1+ 28.Rxf1 and I’m still a piece up. Gratefully, I played 23…Qf6 and White bailed out with 24.Nxh7, but after the intermediate 24…Qf2+ White’s king was in trouble. In the ensuing complications I picked up a piece and exchanged down to an easily winning endgame.

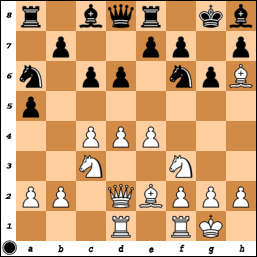

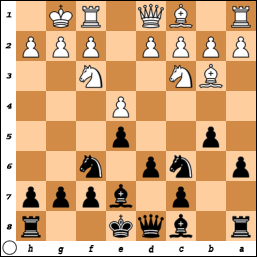

My 2-0 start meant that in round 3 I got to play on board 1 against Mika Brattain, who at 2402 is the third-best 15-year-old in the country. (One of the things I really like about playing in chess tournaments is the way that it totally flattens out lots of differences like age. I’ve literally seen a 90-year-old play a 9-year-old on equal terms.) He played a Najdorf with …h5, a plan that I know a little about but have never encountered myself. The main idea is that it stops White’s g4-g5 plan in its tracks. I thought I remembered that the standard antidote was to push on the queenside, so I did so, but a couple of moves later I was not too pleased to find myself in this position:

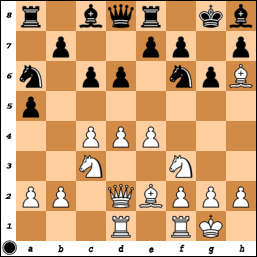

Schmidt 2003 – Brattain 2402 after 14…Qc7-c6

Black is about to get …d5 in with the help of his queen, and then he’ll already have accomplished everything he could have hoped for from the opening. After the game, Mika said that he thought that my earlier a5 was a big mistake because now I can’t push the queen away with Na5. What am I supposed to do, take the rook that I just moved from f1 to c1 and put it back on d1?

Yes, I am! After 15.Rd1! Black’s queen doesn’t have much point on c6, so the tempo loss isn’t a big deal. I can bring my a1 rook over to c1 and everything’s nice and tidy. This has been played 4 times in my database (out of 6 games) and White did fine, winning two games and drawing two. It can be really hard in chess to look at a position with fresh eyes and be willing to basically undo your last move, and I was not up to the challenge here. I played 15.Na4? and after 15…d5 Black was already better, and although I put up a decent fight, I lost in 30 moves.

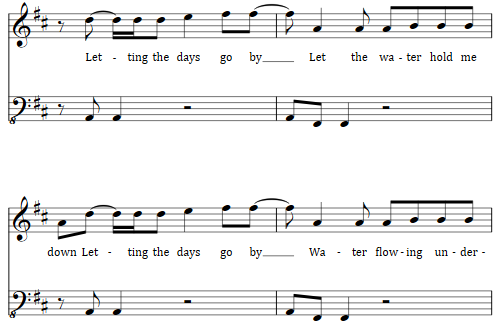

The fourth round pitted me against the wily Tim O’Malley, whose rating is “only” around 1800 but who has a keen tactical eye and is always a threat; in fact, he had already dispatched two higher-rated players this tournament already. I thought that it would be a short game when he fell into the famous “Noah’s Ark” trap (so-called because of that’s how long it’s been around):

O’Malley 1812 – Schmidt 2003 after 7…d6

White played 8.d4? Nxd4! 9.Nxd4 exd4 and now he can’t play 10.Qxd4 because after 10…c5 and the queen moves, Black plays …c4 and traps the bishop.

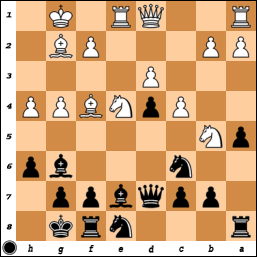

At this point I kind of mentally chalked up the game, but Tim kept fighting, playing for maximum activity, and I found myself having a little trouble getting all my pieces working well, although it seemed like just a matter of time until I could simplify down to a winning endgame, especially since I was up on time 10 minutes to 1 in the following position:

O’Malley 1812 – Schmidt 2003 after 29.Qe5-g5

Probably the easiest way to keep everything under control here is 29…Rd7, protecting against Re7. Instead I immediately tried to trade pieces with 29…Bd5?, and after 30.Bxd5 Qxd5 Tim bashed out 31.Re8+! Argh, it’s the infamous hook and ladder trick, winning my queen for a rook!

After a minute of staring disbelievingly at the board, trying to decide whether to resign, I played on with 31…Rxe8, because hey, at least there’s not a lot of time left on our clocks, so the duration of my misery is limited. Besides, I remembered a fortress pattern from one of the Yusupov books and it seemed possible that I might be able to set it up, especially since Tim only had one minute and probably didn’t know what I was aiming for.

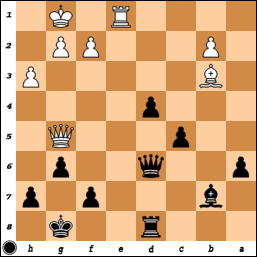

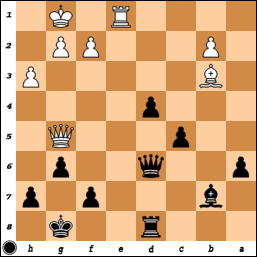

Long story short, I got there 20 moves later:

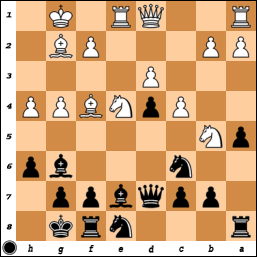

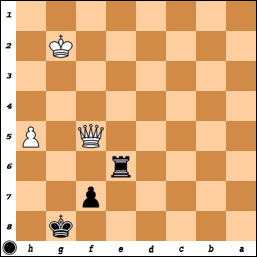

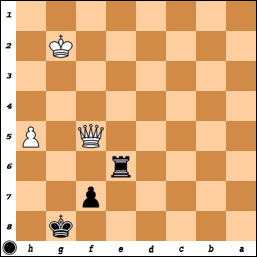

O’Malley 1812 – Schmidt 2003 after 51.Qf6xf5

I wasn’t 100% sure at the time, but according to the tablebases, this is in fact a theoretical draw. I played 51…Kg7 and from that point I can just shuffle my king between g7 and h7 and my rook between e6 and h6 as the situation warrants, and White can’t make progress. It’s very important that my pawn isn’t any further up the board, or there would be room for White’s queen to sneak around from behind. On move 72, with 7 seconds left on his clock, Tim finally gave up and agreed to a draw. I was upset that I turned a win into a loss, but on the other hand I kept fighting and turned the loss back into a draw with the aid of some endgame knowledge that a lot of masters don’t know, so I could be pleased with that. And the spectators enjoyed it!