“Entangled” is the second song on the new record, but Greg wrote it, so I’m skipping to number 3, “Hit On You”.

This album is light on the “funny ha ha” songs, as people have noted, and this is probably the only outright example. I’ve always been a fan of songs in which the backing vocalists seem to have their own personalities – “With a Little Help from My Friends” is the best example I can think of offhand. Something about the other singers referring to me in the third person, as if they’re ambassadors or live translators, tickles me. And then it was natural to have them veer off in the third chorus into their own completely parallel commentary, warning the listener of the ulterior motives of the lead singer. Your mileage may vary, but I think “Pretend you’re gay / or you have the flu” is freakin’ hilarous. (I think this is largely because it’s fitting into a fairly tight rhyme scheme that has already been established.)

The form is kind of unusual: Verse, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Chorus, Chorus. It’s unusual in modern pop music to never come back to the verse after the beginning of the song, but it was a standard technique back in the days of “standards” (Porter, Gershwin, etc.) to have an intro section that never returned, and you encounter it in many early Beatles songs as well, for example “Do You Want to Know a Secret” and “If I Fell”. I wasn’t really thinking of those sorts of songs as a model, though – mostly it was just that I already knew I needed three choruses (one without backing vocals, one with backing vocals added, and one where the lyrics diverge), and probably a bridge, so those were already eating up a fair amount of time, and (probably due to the fact that the choruses are different each time) I didn’t feel like it was getting too samey if I didn’t throw another verse in.

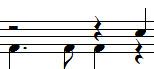

The verses are mostly in 6/4, and I was trying to get our drummer Bill to bring that out with a really emphasized

which he did once and then collapsed cracking up. Uh, why is that, Bill? Oh, yeah, it’s exactly the same as the verses of “Heat of the Moment” by Asia. OK, never mind.

The bridge moves to another key and then back, which is a technique I really like. “Your body’s hotter than the deepest deep-fat fryer” also cracks me up. See, deep-fat fryers are really hot, and this one is even deeper, even though that makes no sense! Is that one of those jokes that becomes less funny when you try to explain it? Sigh. The harmonic transition from F to Ab for the bridge is super abrupt, but I’m really happy with the Ab -Db – G – C – Bb – F sequence (under “I’ve got to buy myself a new pair of pants ’cause my loins are on fire”) that accomplishes the return to F.

This was not a sure bet to make it onto the CD. I was worried with this song, as I always am with the funny ones, that it wouldn’t work well on record, that it’s mostly good for playing live, where people can react to the jokes in real time instead of hearing them over and over; also, because of the laid-back nature of it, it has the potential to sound kind of limp if we’re not really tight. But it ended up sounding really good, and in our final flailing song-ordering pass, I said, “You know what? We could put this right up front,” and I think it works really well there.